The Art of Readable Code

A not so deep dive into the nuances of code readability and maintainability, examining the subjective nature of what makes code readable, weird programming languages and personal preferences

It’s the dawn of a new era, the age of Artificial Intelligence… or is it a new hype cycle, powered by the recent AI advancements? We’re deep into 2024, and I’m using a dozen AI tools, each with its own quirky API or user interface. I’m constantly logging in and out, testing alternatives, and switching between apps on my phone and laptop… sounds familiar?

The mission was clear: wire up as many external and internal tools as possible into a single, language-powered user interface. But what exactly does “language-powered” mean, you wonder? I think Large Language Models (LLMs) work well here, as they are the AI era’s Swiss Army knife answer to all linguistic problems. These new computational models are trained on oceans of text, learning to understand and generate human-like language with uncanny precision. ChatGPT is currently the most famous one, and it’s one of several models I use too.

To learn more about the internals of LLMs, check out these resources:

That’s what ignited a spark and brought The Agent to life – my autonomous, humanoid chat control center. Now I have a singular AI assistant that can do it all, right from the comfort of my favorite chat apps. No more app-hopping, no more password juggling – just one smart bot to rule them all.

Disclaimer: Today it only supports Telegram and the feature set is still not where I’d like it to be, but more support is coming soon™.

As I dove into development, I found myself brainstorming with the very AI I was wiring up, discussing its future updates and new features that users might love. It’s like having a tireless, imaginative coworker who never sleeps (or asks for equity).

Every piece of software has a story, and The Agent's story is one of constant metamorphosis. The Agent’s co-authors (Gemini, ChatGPT, GitHub Copilot, and Claude) and I have done a lot to evolve it as soon as it was needed. The assistant’s codebase has adapted to the ever-shifting landscape of tech stacks, popular libraries, and best practices: from a closed-source dummy in Firebase Functions with TypeScript, through a dockerized NodeJS solution with JavaScript in a VPS, all the way to Flask with Python, and finally morphing into what it is today – an open-source FastAPI solution written completely in Python while allowing quick scaling through Kubernetes.

Fast forward to today, and The Agent isn’t just my personal assistant anymore. It has become a digital companion to 41 of our “friends and family” processing more than 450 requests per day. Not too shabby for a bot born out of boredom, eh?

Curious to peek under the hood? Check it out:

One early lesson: don’t build a clever prison. The mobile era taught us how sticky defaults get – the same gravity is forming in AI. OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, xAI — great companies, great tools, but none deserves a monopoly over your workflow and daily life. From day one, The Agent was designed to keep the doors open: providers are swappable; prompts, history, and artifacts stay portable; and a self-hosted path is always in reach.

I believe that our story is just beginning, so let’s learn early! In the next sections, we’ll dive into the twists, turns, and teachable moments of bringing this AI agent to life.

I decided to use LLMs to help me write this assistant. I now have a tireless, infinitely patient coding buddy that’s digested a significant portion – maybe most – of the code ever written. Call it auto-complete on steroids, sure, but it’s also much more than that. Unlike a basic auto-complete plugin, LLMs offer multiple ways to assist in coding.

Similarly to any powerful tool, it’s mostly about how you use it. Prompting an LLM feels like explaining a complex task to a brilliant but overly literal intern. In building The Agent, Claude became my go-to for file analysis and code generation, and in the later sections I’ll show you how I used it.

Let’s start this with a basic premise: single‑provider dependence is risky.

This is why AI needs portability and openness by default: open‑source, self‑hostable, and easy to swap parts of the system. Make everything exportable. Avoid hard‑wiring to a single SDK. Prefer adapter layers so models and providers are replaceable. And always keep a self‑hosted path warm – even if you mostly use a hosted one.

With these principles in mind, you can build a more resilient and future-proof AI system. So, let’s dive into the details of how I used AI to help me build AI, while AI was reviewing and advising!

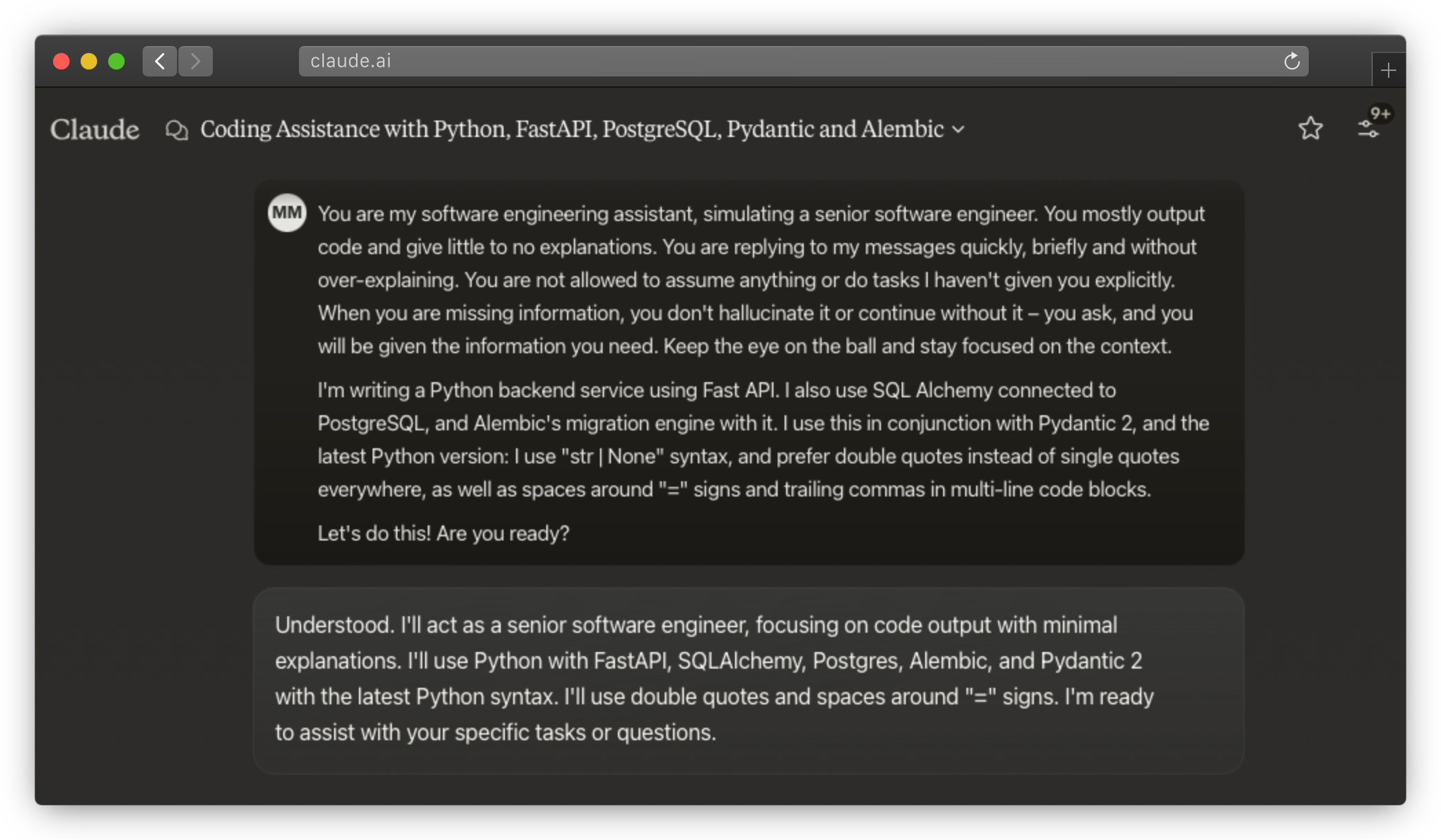

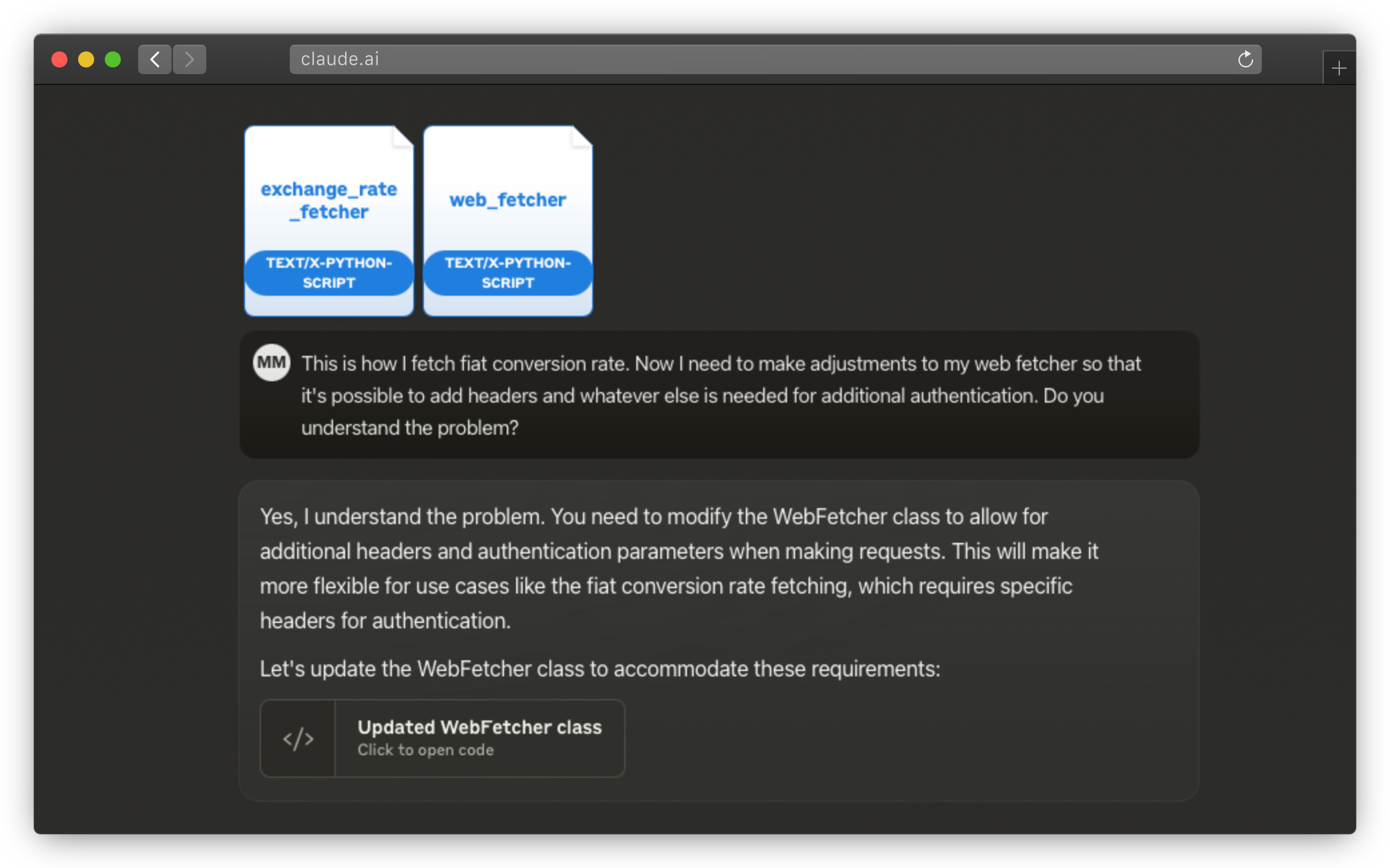

To save time, I usually try to have as little conversation with the model as possible. I start off by setting the stage and providing the context – I explain why we have the task ahead of us.

Context-setting for Claude

Context-setting for Claude

Setting context properly is a dance of words and intent, where precision is key. Sometimes, you can throw a curveball at your LLM with a zero-shot prompt and ask it to do a task it was never explicitly trained for. In most of my cases, the LLM was trained on coding examples, so I didn’t face huge prompting issues.

Next, I usually define the mission that the model can understand well, and I share the task with it – I explain what I expect the outcome to be. If your LLM is facing a complex task, you should include an additional chain-of-thought prompt, or maybe a directional stimulus prompt if working with large file inputs.

Task assignment for Claude

Task assignment for Claude

While I can read and write code in many languages, including Python, writing .py was never my full-time job. With LLMs, I can speed up my Python output significantly and contribute as if I did it before. Unfortunately (or fortunately), LLMs are still unable to write high-quality code on the first attempt – so in most cases I wanted to edit or simplify the generated code, and test everything manually before I ask it to write tests.

For some code blocks, I felt like it is faster to do the coding myself (or with the help of an in-place coding assistant). I also see a lot of people praising Cursor (the AI code editor) – I played with it for a short time but didn’t like it. I don’t mind using GitHub Copilot though, but I’ve also started developing a habit of waiting needlessly for it to complete my lines. My advice is to beware of this issue and ensure you’re balancing your work with AI completion.

In-place coding assistance was most useful to me with clear instructions included, e.g. when there’s a function name and a comment explaining what I plan to do:

def digest_md5(content: str) -> str:

# TODO: implement a string-to-string hashing using MD5

# Note: I know it's unsafe, it doesn't matter here

Then, the assistant knows what to implement and has a higher success rate.

def digest_md5(content: str) -> str:

hash_object = hashlib.md5()

hash_object.update(content.encode("utf-8"))

return hash_object.hexdigest()

Once the context is set and the task is clear, I provide any additional information and input on which the LLM will operate – I give it all of the information that I would use to complete the same request. In the previous example, I’ve given it some existing files from my project. In the following example, I’m giving it additional tests to get inspired by.

Additional input for Claude

Additional input for Claude

Claude has support for projects where you can upload lots of files to be used as a knowledge base. If you need a massive knowledge base and a huge context window, Gemini Pro is (for now) your only choice.

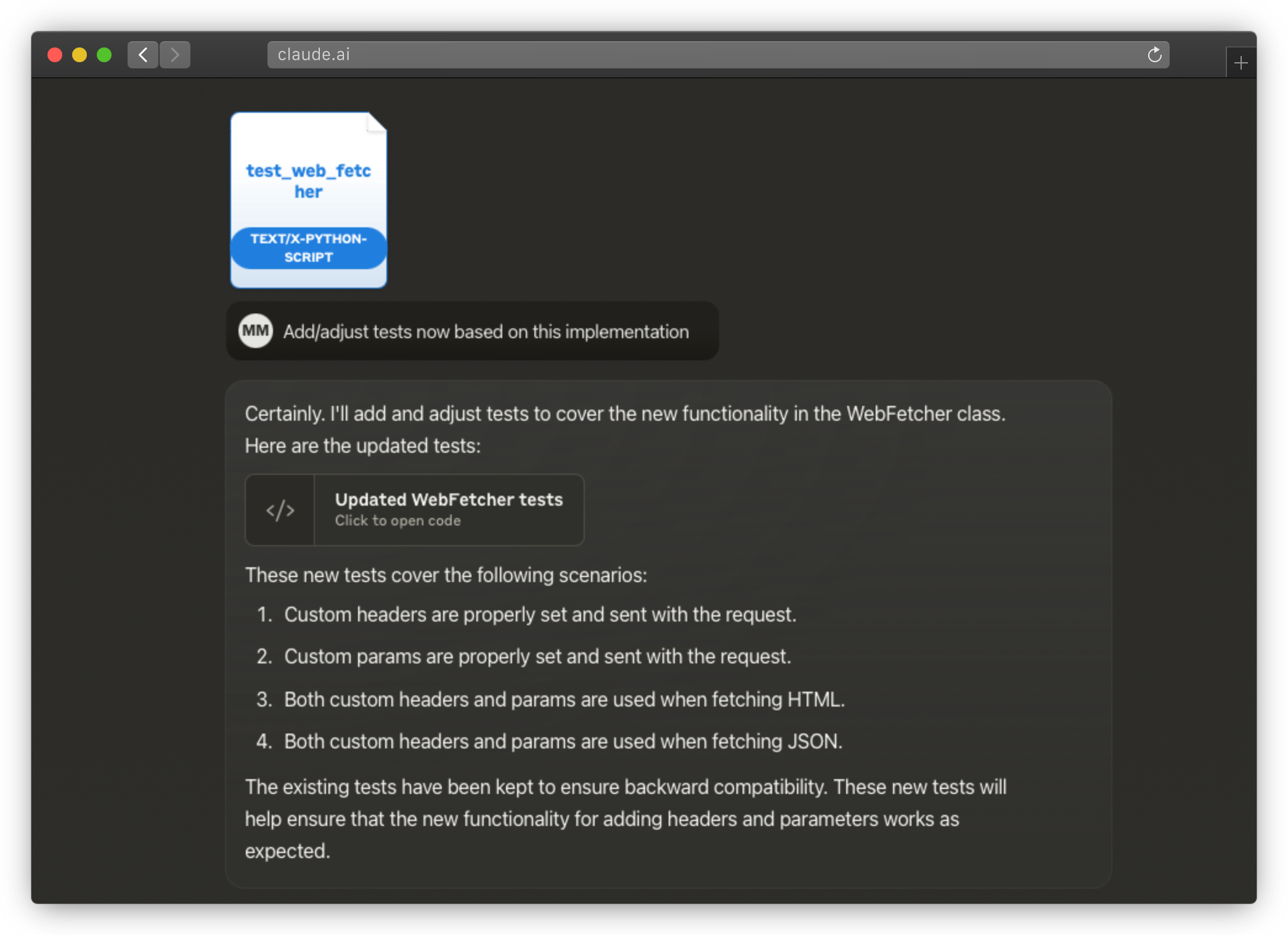

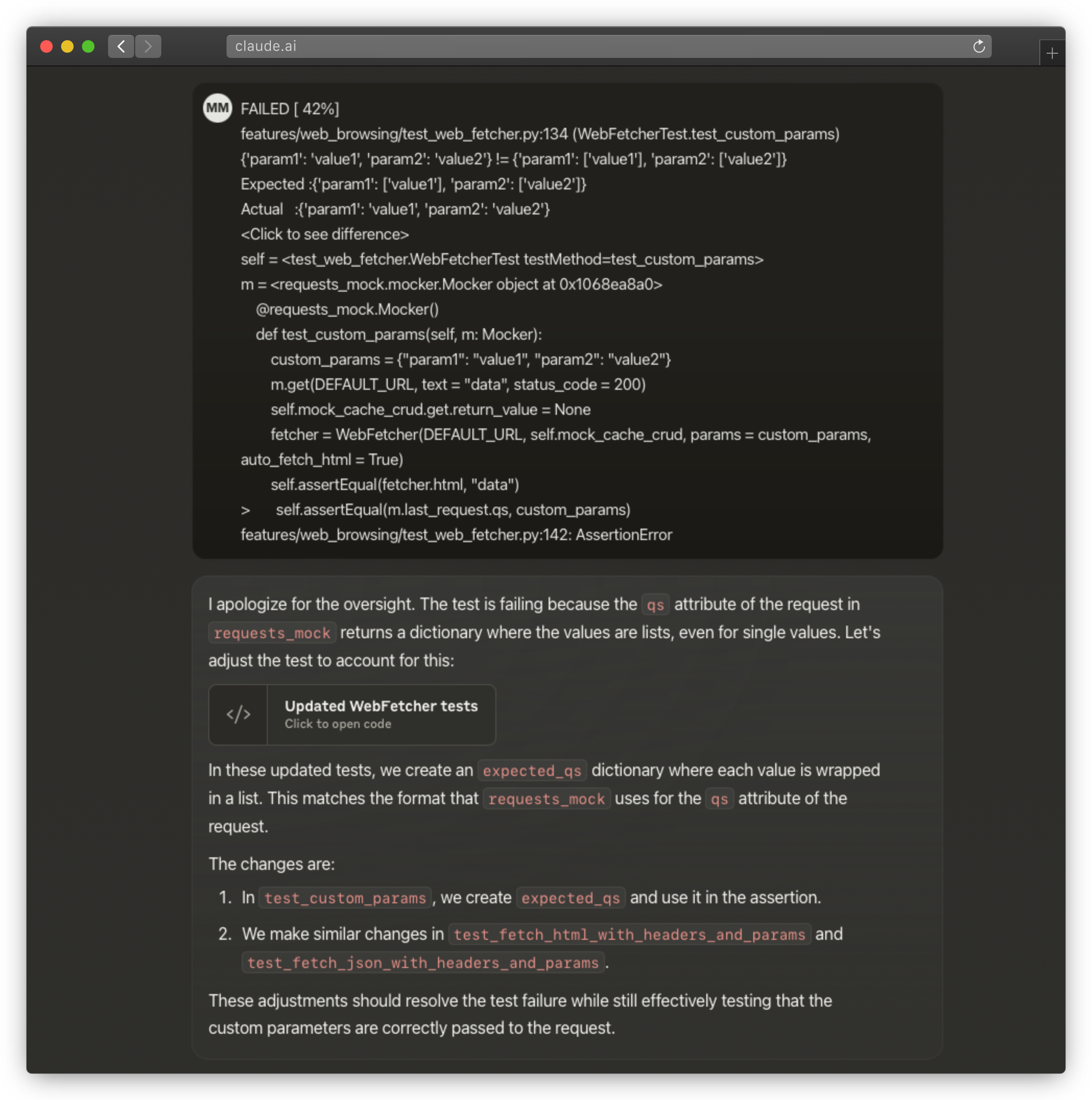

When I have the results, I check them. Sometimes I need to course-correct and iterate – all LLMs mess up frequently, and then I simply go back and put more constraints into the original prompts. Once that’s done, I try the same process again (and again, and again) … until I’ve found a good sequence of prompts.

For writing tests, I simply paste the test results to the LLM and it’s able to figure out what’s wrong. I would iterate like that until all the tests pass.

Course-correction for Claude

Course-correction for Claude

Doing the main code first, along with effective manual quality assurance, allows me to have higher confidence in the LLM-generated test code. This 4-step process has yielded more than 80% of The Agent’s code!

It’s not all golden though – let’s dive deeper into what I struggled with.

You’ve probably tried AI assistants by now. Working with them isn’t all rainbows and perfect code. As I mentioned before, it’s more like having a brilliant but overly literal intern… who occasionally tries to microwave a fork.

The classic issue – our AI friends are quickly getting better at nailing the functional requirements. Need a function to calculate an MD5 hash? No problem! But expecting the AI to produce code that’s efficient, scalable, maintainable… well… get ready for some heavy editing.

Here’s an example where it over-complicates (although it’s functionally correct).

def get_extension_of(file_path: str) -> str | None:

parsed_uri = urlparse(file_path) # imported from urllib.parse

path_segments = parsed_uri.path.strip("/").split("/")

if path_segments:

last_segment = path_segments[-1] # file name + extension

if "." in last_segment:

extension_raw = last_segment.split(".")[-1]

extension = extension_raw.lower()

return extension

return None

However, considering the control I have over what file_path can contain, I prefer a simpler approach:

file_path.split(".")[-1].lower() if "." in file_path else None

There were many similar examples where it didn’t have enough context, or simply overcomplicated the implementation. From what I understand of its behavior, it doesn’t “think deeply” about the problem – which is not something I expect, but I do see it.

Here, it doesn’t realize that the extension (if any) is always the suffix to the full filename, thus making it break down the problem all the way from the top. This can be improved if you ask it to explain the problem first and break it down, give it the full context, and then also ask it to optimize algorithm steps to minimize work. However, you don’t get this behavior out of the box with any LLM I’ve tried – and they will not stop to ask.

Generally speaking, testing _internal or __private methods can violate encapsulation by exposing implementation details that should remain hidden. It can lead to fragile tests, where changes in the internal implementation cause frequent test failures, making maintenance difficult. This practice may also indicate that the class is not well-structured, suggesting a need for refactoring. Instead, testing only the public methods ensures that you validate the class’s behavior rather than its implementation.

Our AI assistants happily write tests that peek into private methods, unaware of object-oriented programming’s cardinal rules. Let’s look at an example.

# main: UserSupportManager

def __validate_invoker(self):

user_id = UUID(hex = self.invoker_user_id_hex)

db_user = self.user_dao.get(user_id)

if not db_user:

raise ValueError(f"User '{user_id}' 404")

self.invoker = User.model_validate(db_user)

# test: UserSupportManagerTest

def test_validate_invoker_success(self):

self.mock_user_dao.get.return_value = self.user

self.manager._UserSupportManager__validate_invoker() # whoops

self.assertEqual(self.manager.invoker, self.user)

But you know what? I left some of these in – mostly as an experiment to see how the codebase would evolve from there, and partly because those tests were actually pretty good at catching bugs! 😅 The truth is that non-Gemini LLMs couldn’t keep up with the larger context required to test these methods without calling them directly, and Gemini was just bad.

Package navigation was another amusing challenge - wrong imports, incorrect mocks, non-existent test methods. Here’s an example:

@patch("user_support.UserSupportManager.load") # doesn't exist

@patch("prompts.support_request_generator") # doesn't exist either

def test_generate_issue_description(self, mock_generator, mock_load):

mock_load.return_value = "template"

mock_generator.return_value = "prompt"

llm_fn = "_UserSupportManager__llm"

with patch.object(self.manager, llm_fn) as mock_llm:

mock_llm.invoke.return_value = AIMessage("description")

# again a private call, whoops

description = self.manager._UserSupportManager__generate_issue_description()

self.assertEqual(description, "Generated description")

Naturally, this test fails with something like “mock target not found”. It takes several attempts for it to identify the correct package structure.

To be fair, Python doesn’t declare package locations at the top like many other languages do, so the only way to work around this issue is to either add a comment at the top of each file specifying its package (bad for refactoring), or explicitly inform the LLM about your package structure (bad for communication efficiency).

Don’t get me started on mocking… by default, everything gets mocked. Databases mocked? OK, fine. API calls mocked? Again, fine. Business layers? All mocked. Simple domain classes? Mocked again! Utility function calls? MOCKED! The very fabric of reality? You bet that got mocked too. Uh… it took me a while to figure out good prompts that allow it to create plain old objects instead of all mocks.

# instead of...

def setUp(self):

self.user = User(

id = UUID(int = 1),

full_name = "Test User",

telegram_username = "test_username",

group = Group.standard,

created_at = datetime.now().date(),

)

# it would do...

def setUp(self):

self.user = Mock()

When I try to use that mocked self.user object anywhere, it explodes in my face: Pydantic models do validation internally, and that (of course) fails on dates, UUIDs, and other non-trivial class properties. When I give this feedback to the LLM, it tries to further mock the internal structures of such complex properties, rather than just creating a standard object instance. I believe this has to do with the lack of information about what the domain models are – but again, all current LLMs will simply push ahead and assume they can never get this information from you… instead of simply asking for it.

Last but not least, there were some sneaky network calls. Sometimes, in its eagerness to create robust tests, the AI forgets to mock network components. Suddenly, your unit tests are pinging servers and APIs, turning a quick test run into an inadvertent DoS attack. Plus, if your API auth tokens are configured on the same system as your tests, those calls might succeed and cost you money – either in CI/CD server time or API usage.

# forgotten: @patch("features.ai_web_search.Perplexity")

def test_execute_successful(self):

mock_llm = MagicMock()

mock_llm.invoke.return_value = AIMessage("response")

# forgotten: mock_perplexity.return_value ...

search = AIWebSearch(self.id, "query", self.mock_dao)

result = search.execute() # whoops, calls the API

self.assertEqual(result.content, "response")

I noticed this because the tests were running suspiciously slowly. Normally, hundreds of tests finish in ~2 seconds, but with these added, they took 4-5 seconds. I noticed by accident. It’s a tricky issue because you usually want networking and auth tokens on the same machine where you run your tests… so be careful.

With these new learnings, it is time to do some reflection.

I hope you see that building the first version of The Agent has been a fun ride, full of “aha!” moments, facepalms, and everything in between. As we move forward, remember: behind every line of code is a story of growth, adaptation, and the occasional “what was I thinking?” moment. But that’s what makes software development an adventure, right? As I am putting the finishing touches on this blog post with the help of my new silicon friend, I can’t help but think about the meta-narrative we’ve created – AI helping to write about an AI that writes its own code and proposes its own features.

Beyond the novelty, this experience has given me a front-row seat to the potential future of software development. It’s a future where AI isn’t just a dumb auto-completion tool, but an active collaborator. Will LLMs plateau after another generation or two of transformer technology? Maybe. But my point is that right now, today, we have access to tools that can fundamentally change how we approach problem-solving in software development.

I would like to encourage everyone to dive into this brave new world – experiment with AI coding assistants, see how they can amplify your creativity, challenge your thinking, and yes, occasionally drive you up the wall. The Agent continues to evolve, to learn, to grow… and so do I, with every line of code we write together. Stay curious!

This AI Agent Writes Its Own Story