This AI Agent Writes Its Own Story

A software development experience building an autonomous AI agent using AI coding and brainstorming assistants - the benefits, challenges, and insights gained

A few months ago in a galaxy far, far away… we had a team discussion about trying out Kotlin Coroutines in one of our Android projects at Blacklane. As usual, there are lots of pros and cons when considering a library, technology, tech stack, architecture approach, etc. Specifically for us, but probably also similarly to your situation, our codebase is heavily dependent on ReactiveX – especially the network layer – and having so many ReactiveX constructs everywhere has become a big concern. Recently, a decision has been made: we obliged ourselves to invest a serious amount of time and research Kotlin Coroutines. I did a bunch of experiments with Coroutines on my own since then, and this post is about my journey into Coroutines, some results of my research, what I learned, some other random thoughts – and finally, where to go next if you wish to follow the same path.

So, we’re using ReactiveX a lot. In our JVM code, that’s RxJava + RxKotlin. What’s wrong with that? Is there something wrong at all? Do we really need yet another approach to “async programming”? Well, according to JetBrains, yes.

Disclaimer. I’m going to try and be unbiased here. I’m not saying that Coroutines are directly comparable to ReactiveX because they technically do different things (except for Flow and Channel extensions). Also, I’m not saying that either approach is better at doing network requests and request post-processing. It just happens that we have all of our Android “async” code wrapped in ReactiveX constructs at the moment, and this is probably the most common use-case to observe and “convert” to Coroutines. Therefore, most of my examples are from Android’s presentation or network layers, and the related use-cases.

Let’s start with a bit of history.

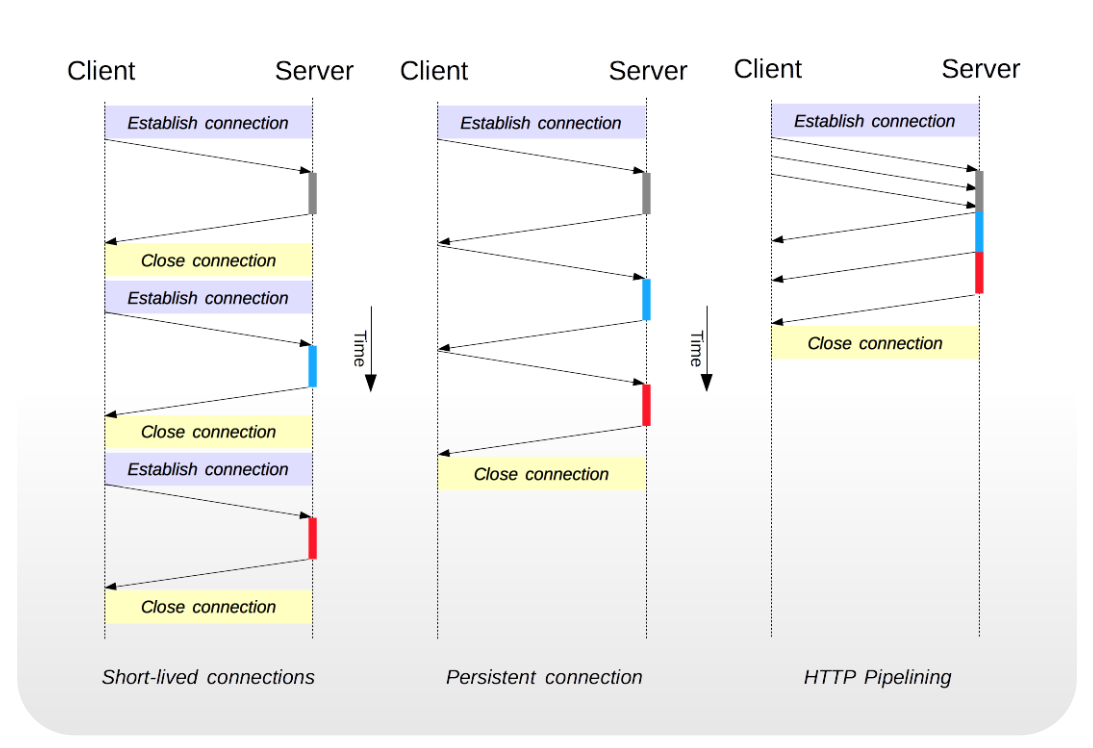

In the old days of Android, in order to process long-running operations (like network requests) or schedule background work, people used AsyncTasks, plain threads, Android’s looper (message queue), different callback approaches coming from SDKs, Loaders, background services, etc. There were a lot of solutions, and there was a lot of abuse of these constructs. Even though all of the mentioned approaches are still available in the platform (and still work!), all of them have some downsides.

Network calls example

Network calls example

AsyncTasks are difficult to maintain due to frequent context destruction, and it’s very easy to forget about the cost of SAMs, memory leaks, parallelization, etc. AsyncTasks are also not easy to cancel/stop in a thread-safe way.

Similar issues arise from using Loaders, although there we had a bit of improvement in terms of cancelation and memory management. But they were still context-bound.

Plain old (good old?) threads are considered heavy-weight in mobile operating systems, thus we always prefer to create as little of them as possible (2 per CPU at most). To work around the low-CPU and low-memory issues, we used thread pools. Thread pools usually need to be managed manually.

The most popular callback approaches (not all though) tend to cause what is known as “callback hell”. This problem is especially apparent in legacy and native SDKs. Often, callback-based SDKs just lead to a poor client implementation due to having poorly designed APIs in the first place. Maintenance of client usages becomes more complex when refactoring the SDK.

Using Android’s loopers is prone to causing memory leaks, and is also cumbersome. Task cancellation using loopers is not straightforward and also requires thread and runner management.

Using Android services… well, they are slow to start compared to the approaches above, they usually require attaching and detaching mechanisms, they unnecessarily stay alive for longer (and drain battery from the background), and they have lots of access restrictions (no access to user interface). Having seen a lot of different codebases, it seems to me that most of the service abuse occurs when services are used for processing one-off tasks or for app state management. This is quite frequent in teams who are new to Android and are not used to Android’s stateless nature… I guess the learning curve is not so flat.

And finally, I don’t want to forget one big thing: the headache that comes from building your own “async” framework, creating something completely thread-safe, yet performant… and then trying to cover that multi-threaded behavior with tests. Trust me, I’ve done it, you don’t want it.

Let’s start with this: we definitely don’t want too many possibilities for making a mistake. That’s for sure. Too many tools means too many approaches. We want something easy to use, with a sensible default behavior, clean API and good documentation… and if the core platform won’t help, the open-source community will come to the rescue.

Project logo

Project logo

As you probably know, ReactiveX is a collection of mature open-source streaming libraries, allowing the users to shoot events into different types of streams, modify the resulting streams’ behavior, and finally react to those modified events in a single place using the straight-forward callbacks. What is very interesting with ReactiveX is that it provides fine control over event execution threads (at least for RxJava it does), which allows the user to effortlessly switch between different threads or thread pools. Easy thread switching is something we’ve been using (and abusing) for years on Android… having it was really handy for processing network requests.

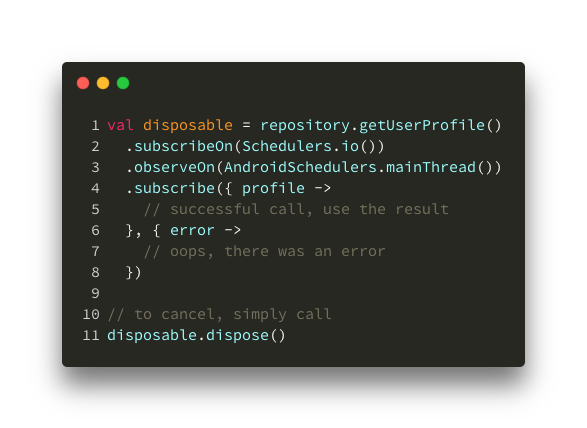

Here’s a simple example of what ReactiveX network fetch looks like:

Fetching a profile

Fetching a profile

ReactiveX works. Why change that, right?

We can surely agree on a couple of things – ReactiveX is a huge package to include in your codebase (although slimmer with ProGuard/D8), it has a really steep learning curve, and we abuse and misuse it in many ways due to its many, many features. On the other hand, Kotlin’s Coroutines come in a slim package by default, syntax support is built-in, and they make your asyncronous code look synchronous (which helps with code readability). Or, at least, that’s what JetBrains wants us to think.

How far is their marketing pitch from the truth?

In simplest terms, a Coroutine is a runnable task, a block of code that will be recognized by the Kotlin’s compiler as a Coroutine, and either be immediately executed or scheduled for a later execution. Despite the overwhelming number of comparisons to threads, Coroutines are not threads. Coroutines do run on Threads though, in well-organized thread-local event loops. The process of scheduling Coroutines for execution or switching threads while executing is called “dispatching”.

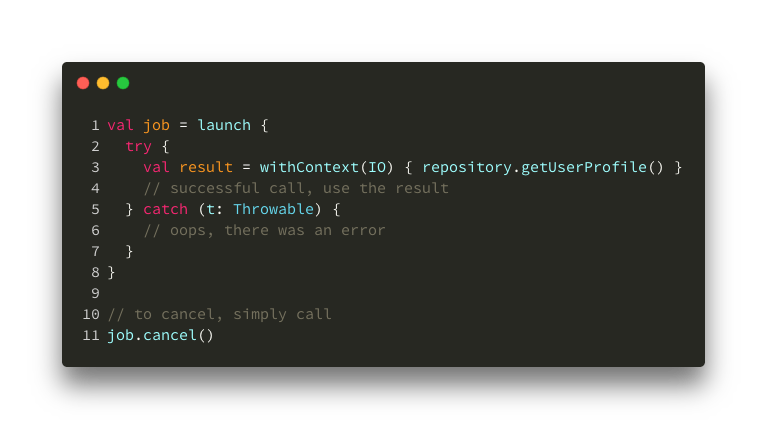

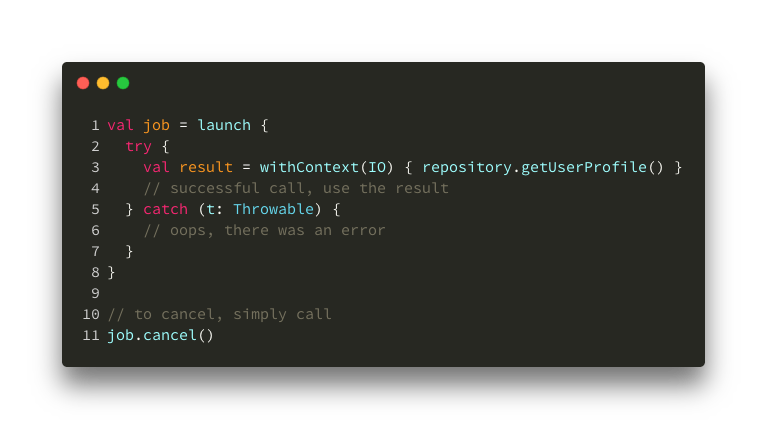

Here’s a sample of what that same code snippet from above looks like with Coroutines (the launch lambda is basically a Coroutine block):

Fetching a profile

Fetching a profile

Looking back at that piece of code, one could argue that this approach is better because we eliminated callbacks completely, we can easily switch the thread for our network call, network code block looks like it’s synchronous, and in case of an error we would get a clean stack trace pointing to the exact invocation site. In this example, I’m using launch, withContext(IO), job and cancel() concepts from the Coroutine world, more on all of these later.

This code snippet is actually not copy-paste-ready. To be able to run Coroutine blocks and switch threads using this framework, you need to set up a Coroutine environment around your Coroutine block. This is often misleading in online tutorials and marketing materials.

Other than the environment setup, you also need to include an additional core package (very small) to be able to fully utilize the dispatching functions and new Coroutine builders.

For Android, you’ll need a tiny Android package to be able to use Android’s Main looper as a Coroutine dispatcher.

Unlike threads, Coroutines can’t just start from anywhere. They need to run in a very special environment that contains all of the necessary information about each Coroutine running inside of it, for example: which threads Coroutines run on, how they complete, how they cancel, whether some Coroutine blocks failed or not, and so on.

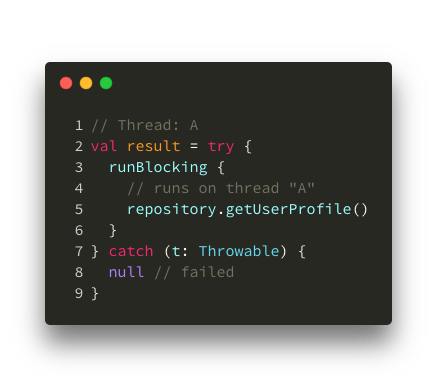

If you want to force a Coroutine to run in-place – outside of that kind of “environment” – you can use the runBlocking function to synchronously execute the Coroutine task on the current thread.

Running in-place

Running in-place

Now, let’s see how to launch Coroutines from a proper environment. I’ll try to simplify what the most important components of the environment stand for.

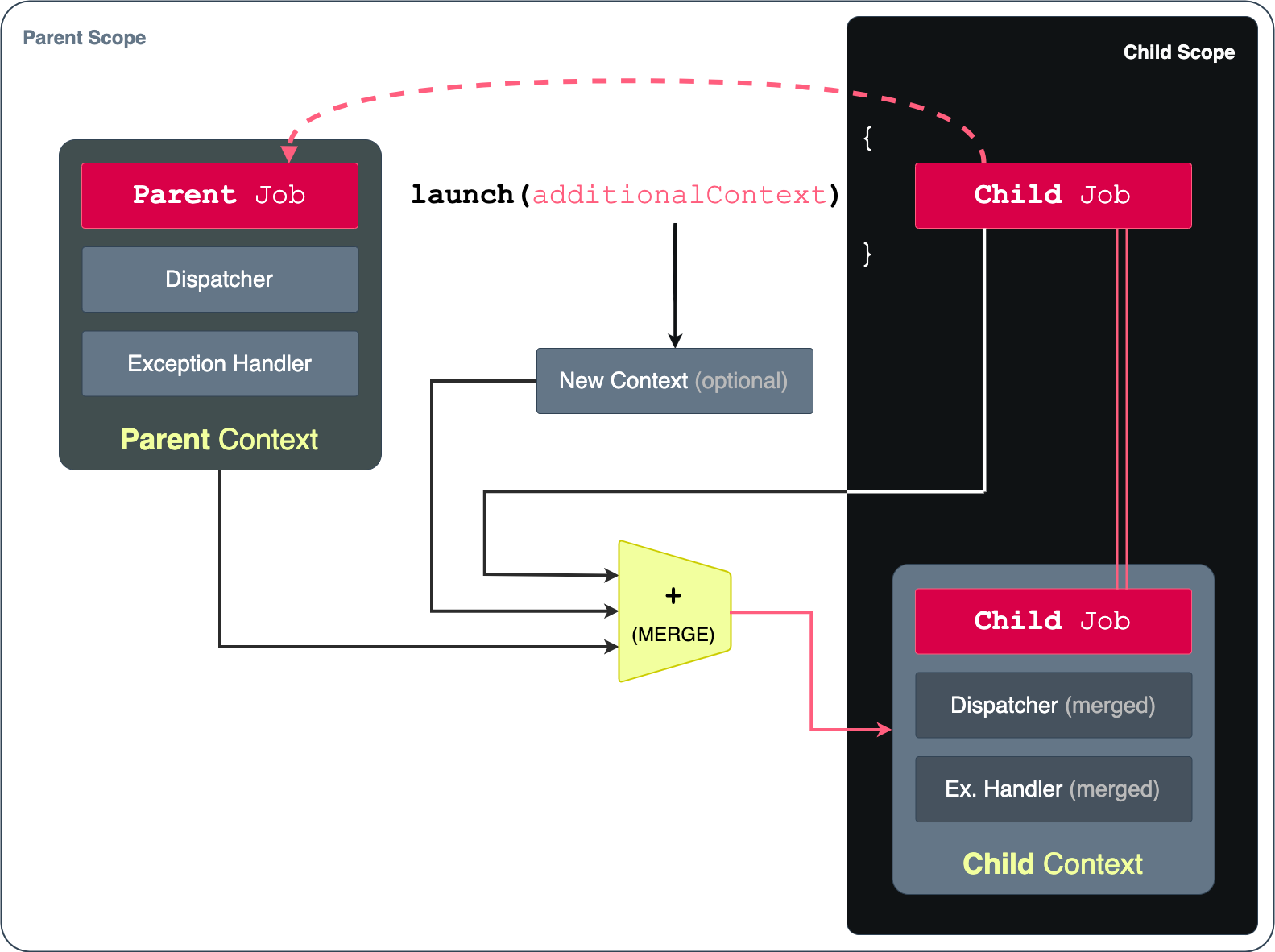

Element – Specifies rules about the environment like on which threads to schedule Coroutines, how to cancel running Coroutines, how to handle Coroutine exceptions, etc. Elements basically store “rules” of the environment, but can also contain meta-information about it, or even an controller for managing running Coroutines (called a Job). The meta-information about running Coroutines can be things like “name” or “label” or similar things your coroutines might need.CoroutineContext: A collection of one or more Elements. Basically, it’s a bunch of environment constraints and rules stored together. Every individual Element is also a CoroutineContext itself (very clever), so we are allowed to use the + (plus) operator function to add different Elements together and thus form the final CoroutineContextCoroutineScope: The more technical name for the environment that’s ready to launch Coroutines. Its main job is to hold the CoroutineContext (environment’s set of rules) and make it easily accessible using the coroutineContext property.Bonus fun fact: the CoroutineContext keeps all of its Elements in a structure similar to a map. If needed, you can access these environment “rules” (Elements) using the built-in map keys, e.g. Job, CoroutineName, etc.

When you’re already in a CoroutineScope (the environment), you can use Coroutine builders such as launch to dispatch new jobs into the environment. The jobs run using the set of rules (Elements) specified in the Scope’s Context.

Let’s look at this example again.

Pay attention to withContext

Pay attention to withContext

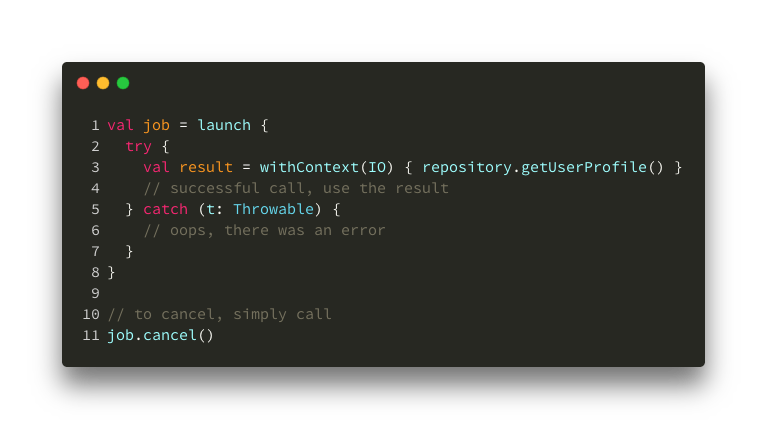

And there’s more. Launching new Coroutines from that same Scope allows specifing additional or new “rules” (Elements) inline. Coroutine builder functions such as withContext allow you to override the Elements already set in the root Scope. So, for example, you can decide to only replace the thread into which the new Coroutine is going to launch. The Coroutine builder function will then smartly merge the root Context with the provided new Elements – forming a new Context for your new Coroutine.

Let’s take another look.

Pay attention to withContext

Pay attention to withContext

Having this override feature is why you can simply “switch Context” using only one argument in withContext(IO). The function will pull the rest from the root Context. IO there is an Element that provides dispatching information, i.e. tells the Context to launch Coroutines in the IO thread pool. It doesn’t have to be only IO though. You can specify multiple new “rules” (Elements) by simply using the + operator between them – because, as mentioned before, all Elements are sub-types of CoroutineContext, making it easy for builders to merge and create new Contexts.

Therefore, the Scopes are structured in a hierarchy. Relationships inside the Coroutine-aware environments look something like this:

Scope vs. Context

Scope vs. Context

As shown in the graphic above, a relation is created between the root Scope and any other Scope created from within. This connection is called a parent-child relationship, as expected. It allows for creating complex hierarchies of Coroutine Jobs.

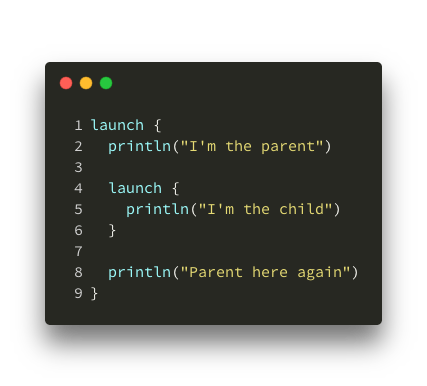

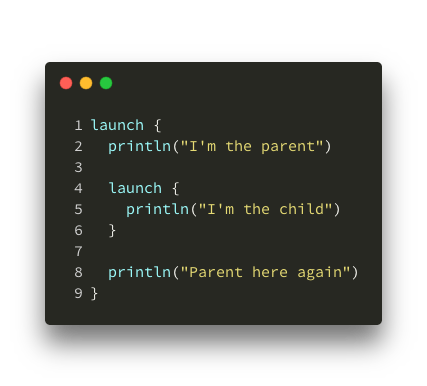

Here is a very simple example of a parent Coroutine creating a child Coroutine:

Parent and Child Coroutines

Parent and Child Coroutines

Similarly to most functions, a Coroutine can have two outcomes – success and failure. Success is the path that returns a value or completes without exceptions, and failure is the path that throws an exception and doesn’t return a value. Let’s observe the failure path.

After a parent Coroutine creates a child Coroutine, their Scopes are bound together. We observe two types of failure:

Parent Coroutine fails (throws an exception)

Child Coroutine fails (throws an exception)

Any Coroutine created using the launch function will immediately return its Job. A Job is an Element of the Context, and allows you to control the Coroutine’s behavior. For example, you can cancel it using that Job.

Parent and Child Coroutines

Parent and Child Coroutines

In the same scenario as above, if a parent Coroutine is creating a child Coroutine, we can observe two types of cancelation:

Parent Job is canceled

Child Job is canceled

Important to note. I thought that a failing child wouldn’t also fail the parent… but that’s what happens by default. Luckily, this behavior is easily changed.

When setting up your Scope and Context, you’ll usually manually create a Job Element to be able to cancel the Coroutines launched from that Context’s Scope. And here comes the trick. Instead of using the default Job type for your root Scope, you should use a SupervisorJob. With this special type of Job, your parent will not get canceled when any of the child Coroutines fail (throw an exception). Additionally, you will be able to use the SupervisorJob to cancel all of the child Jobs without canceling the parent itself. That’s done using the SupervisorJob::cancelChildren() function.

This way, you can have a “supervisor” parent to all of your child Coroutines within a Scope. The parent then “survives” all child failures and cancelations. A supervisor parent only fails when an exception is thrown directly from the parent. Supervisor parent only becomes canceled if you explicitly call Job::cancel() on it, while SupervisorJob::cancelChildren() is additional functionality.

Plain old threads can, of course, block execution. Due to how Coroutines framework arranges its running jobs, “suspending” in the Coroutine world means something like “stop the current Coroutine here, and try to run other Coroutines that are not suspended”. It’s more of a “pause” than a “block”. Therefore, if you have a lot of running jobs, and some of them get “suspended” mid-way, it doesn’t mean that everything stops or blocks until the suspended jobs complete – in fact, it means that (based on the number of threads available to Coroutines) other jobs might start running in place of the suspended ones.

Let’s imagine an example.

Normally, calling launch will only give you a Job reference. It won’t carry any result value with it. To block further execution and force the given Job to complete before the Coroutine continues, you can call join() on the Job. This will make your current Coroutine “suspend” and wait for the jonied Job to complete.

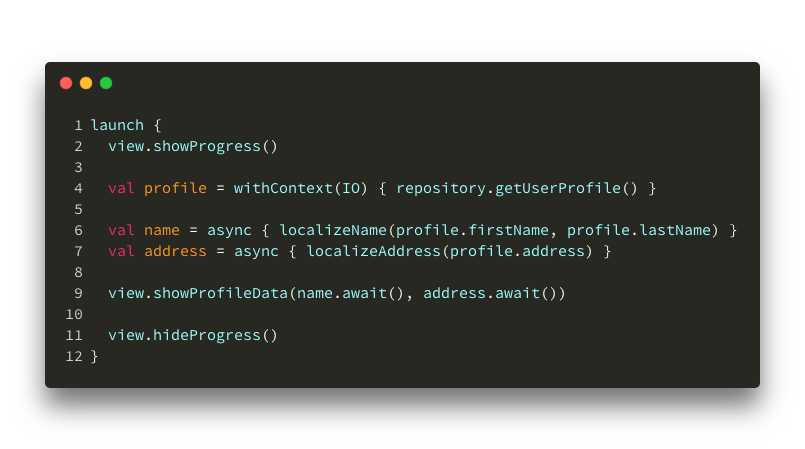

In case you need a real value as a result of a Coroutine (remember: launch won’t give you one), you can use withContext() or async() Coroutine builders. Using async() is very convenient for decomposition of work and parallelization, because it returns a Defferred type of Job (similar to a Future) on which you can call await(). Calling Defferred::await() behaves similarly to Job::join(), it “suspends” the current Coroutine and waits for the result to come. Kotlin’s withContext() is a special case (a suspending function), so there is no way to call join() or await() on it – instead, it is marked as a suspension point for the compiler using the suspend keyword.

Declaring a function suspend fun will instruct the compiler that the code in your function might have to suspend at some point. Where is suspension going to happen? Well, in the Coroutine that invokes your suspend fun function. So, not in the function itself, but outside of it.

There are 2 interesting consequences to this rule:

A suspend function can only be invoked from another Coroutine, because only Coroutines know how to “suspend” (vs. “block”)

A suspend function’s body always has access to the CoroutineScope that is running it, again, because only Coroutines know how to “suspend”, and Coroutines only run in Scopes. This is important because you will be able to access your Job’s isActive property directly from your suspend function. In case of isActive being false, you should stop working immediately, assuming that your host Coroutine has either failed or was canceled.

Take a look at this example:

Suspending and running async

Suspending and running async

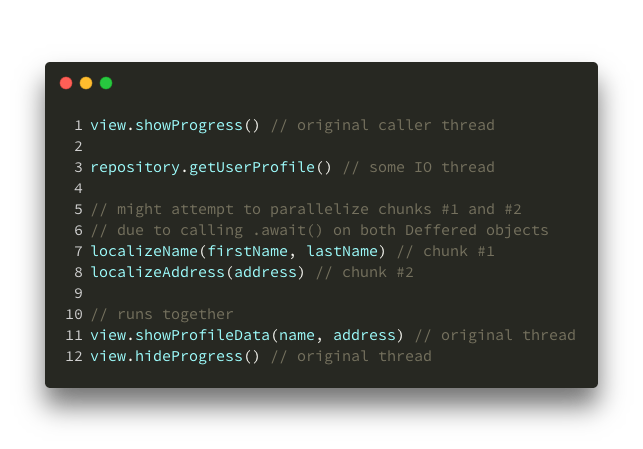

In this case, the compiler will most likely decide to split the work into 4 or 5 smaller tasks, like so:

Suspending and running async

Suspending and running async

The code that Kotlin’s compiler generates will have these 4-5 pieces separated by suspension points and ordered sequentially in a state machine. The whole launched Coroutine will get split and suspended in the correct order to have all the data available in the order required.

Under the hood, this kind of behavior is achieved at compile-time, by adding an extra Continuation function argument to all suspending functions… but that’s a topic for another day.

Having in mind the hierarchical nature of Kotlin Coroutines, dispatching capabilities, and other CoroutineContext features, you can construct a smart Coroutine environment (Scope) with sensible defaults that work on any platform. Coming from the Android project most recently, I’ll be able to give you examples from the Android side of things… but it’s really very similar even if you’re working for desktops or backend services (see: Ktor for native Coroutine support).

As a good rule of thumb, try not to enforce threads/dispatchers/schedulers in repository layers – this takes away control from the caller and makes testing more difficult. You could still do this, but my examples will assume that repositories don’t have any runtime awareness.

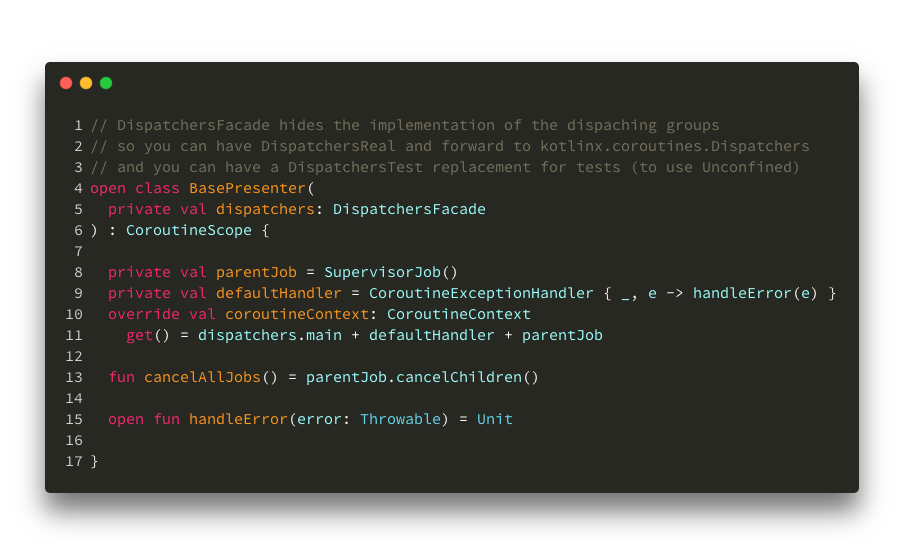

Alright, so we know that a CoroutineContext is constructed out of one or several Context Elements (rules or meta-information). It is an essential part of the Scope. Let’s look at how this would work in a Presenter component.

When I say that I want my environment to contain “sensible default” rules, in terms of Android this means:

1. Explicit threading control. My work should start on the Main thread, as I might touch the UI (to show a progress bar, for example). I will specifically go off the Main thread when I need to.

Dispatchers.Main as my default dispatcher in the root Context2. Easy exception handling. A default exception handler needs to be attached to all of my Coroutines, simply to avoid app crashes.

CoroutineExceptionHandler is a context Element as well! So, I can just add it to my root Context3. Act as supervisor. I will definitely run multiple Coroutines in parallel, and I don’t want to stop all other (unrelated) jobs if one of them fails.

SupervisorJob to get this behavior out of the boxOf course, you can create a CoroutineScope in any class. In these examples, it made sense to have a configured Scope in my Presenter’s class directly.

A base Scope configuration

A base Scope configuration

You might remember that all Context Elements are stored in a map-like structure. When launching new Coroutines, the child Context is a merge between the parent and the newly provided Context Elements. This behavior allows us to keep all of these defaults in the root scope, forcing inheritance for child Coroutines. Easy!

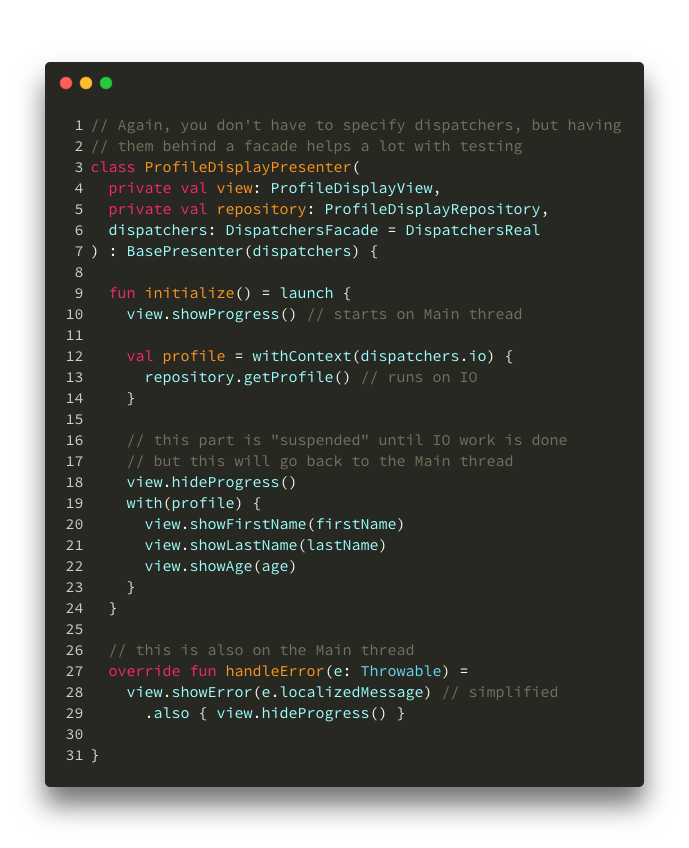

For getting off the Main thread, we would be able to use withContext and replace only the dispatcher for those heavy tasks. In other cases, we could replace only the exception handler to intercept errors and handle them in a special way.

Assuming your UI’s onStop() lifecycle callback will invoke your Presenter’s stop() function, you would be able to call your supervisor Job and cancel all child Coroutines directly from it.

A more complete example of what a “real” Presenter would do is below.

A “real” Presenter

A “real” Presenter

Now, because our base Scope has been configured to push new Coroutines onto the Main dispatcher (unless specified otherwise), Coroutines will start and finish on the Main thread. Our default exception handler will get exceptions also on the Main thread.

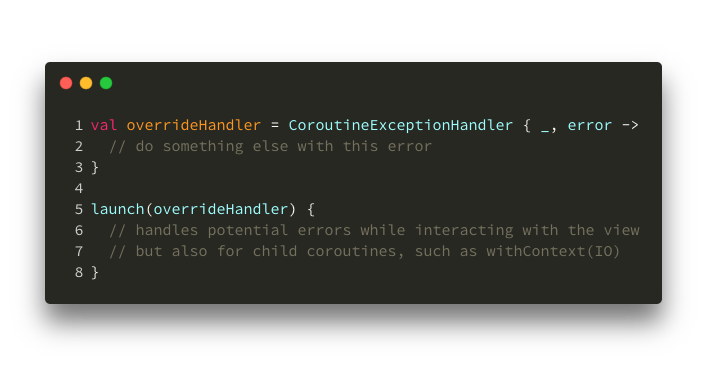

In case you need special error handling for a certain use-case, you can override the exception handler for that Coroutine in a couple of ways.

Here’s an example of replacing a handler to get all errors for a Scope:

Overriding an exception handler

Overriding an exception handler

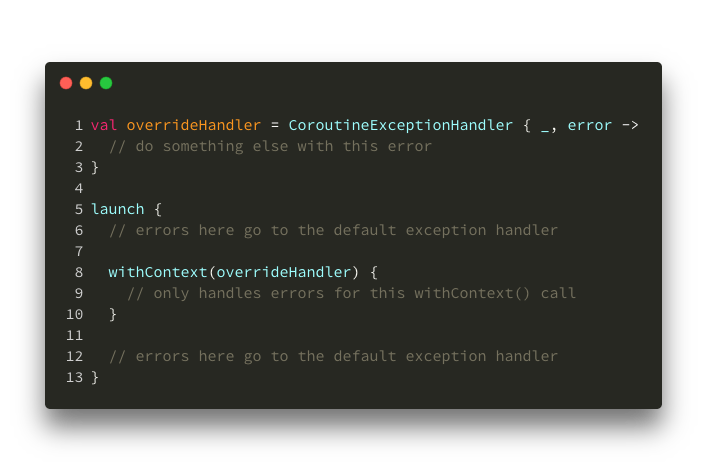

Then, in case you want to handle only sub-Scope’s errors:

Overriding a sub-scope’s exception handler

Overriding a sub-scope’s exception handler

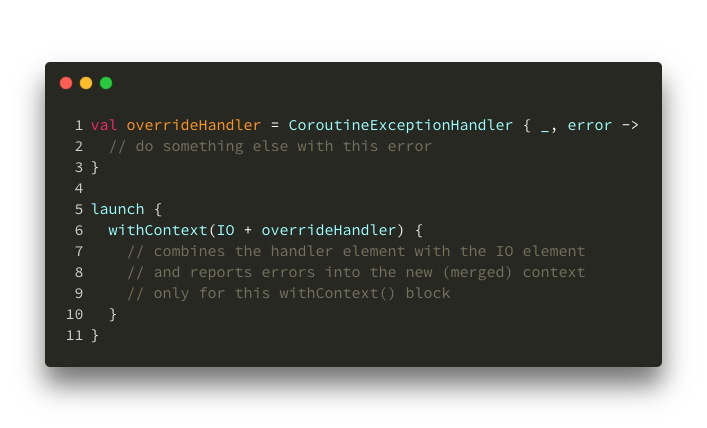

Another example – if you want to override more than one thing from the new Context (remember that trick?):

Overriding threads and exception handler

Overriding threads and exception handler

Having no exception handler anywhere will crash your app. 🙂

You might be misguided by the shortness of this section… it’s not that I believe that testing is not important, but testing Coroutines actually turned out to be quite straight-forward for us.

Once we replaced all of our dispatchers for tests with Unconfined dispatcher, and wrapped our tests in a runBlocking (or runBlockingTest) builders – Mockito, BDD plugins, Hamcrest and its matchers, and all of the other test-related stuff worked the same way as before.

On a side-note, people are praising MockK for its Coroutine support, but I was happy with how Mockito worked and didn’t have any issues… so I haven’t tried MockK yet (especially after this PR).

If you want to learn more about testing Coroutines, you can check out this Google I/O talk or this thread on KotlinLang.

Was this journey into Coroutines valuable? Yes! Every lesson is valuable. But it was also fun to see and try something different.

Are we migrating all of our layers to Coroutines? Yes, slowly. Retrofit supports Coroutines now out of the box, and you can easily convert simple calls from ReactiveX to Coroutines using this official conversion package. Using that, you can migrate gradually, test and verify critical behavior.

Update: our migration took a developer-month to complete, on the guest app and the 21 different screens we have.

All things considered, it’s not that difficult to start. I do think that there is no strong reason to have to switch right now, especially if you have other priorities. It felt kind of weird in the beginning without having to call “subscribe” on chains… or without having to provide callbacks for success/failure. After a couple of tests and experiments (and a bunch of consistently successful Unit tests), you build confidence and things become more natural.

Sadly, the online resources I found so far were super confusing… that’s why we have this long introduction in the first place. If you decide to try out Coroutines, good luck and I hope this post helped!

There’s more!

I created a sample project that tests behavior of different situations with Coroutines. If you’re interested in seeing some weird stuff, go check it out.

I can also recommend this talk by the Coroutines author (although I find him really confusing to listen to). Maybe his blog posts such as structured concurrency, context and scope or blocking vs. suspension are easier to understand. 😬