This AI Agent Writes Its Own Story

A software development experience building an autonomous AI agent using AI coding and brainstorming assistants - the benefits, challenges, and insights gained

This post is just one part of my Time Management series. I really recommend you read the whole series if you have time, but I’ll do my best to make this part self-contained.

Important disclaimers are also included there.

More controversial opinions: ✅

There are a few things I consider when setting goals for myself and my organization[s]:

What do you disagree with the most?!

Either way, I think I can justify most of the things I just wrote, even though my framework isn’t great. 😄 But it’s a good starting point if we’re looking for a reliable algorithm to prioritize tasks, I think.

So what are we looking for?

fun findPriorityItem(items: List<WorkItem>): WorkItem {

// FIXME: This is what we're looking for

error("Too hard to implement")

}

Visualizations are nice, but let’s also clarify. Remember that all classifications here are relative and not absolute, we’re always comparing work items to other work items on the table.

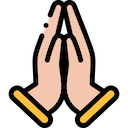

The Priority Matrix (Nike don’t sue me)

The Priority Matrix (Nike don’t sue me)

As Sofija mentions here, this is a variation of the Eisenhower Matrix. Let’s see how my interpretation differs.

1. Urgent, but Not Impactful: “Just do it.”

These are the things I really don’t want to do, because I don’t think they’re important (yet). But these things tend to escalate quickly if ignored. For example, my day-to-day work includes updating security libraries, understanding a rare bug in the Canary deployment, investigating a sudden drop in analytics events, checking on a spike in costs, approving access requests, etc. I usually force myself to do these things right away if they’re small, because small things get done quickly and don’t mess up my schedule at all. Waiting can cause them to be moved to the next category here, which I don’t want. If the work items are large, they must also be impactful (next category) or simply divided into smaller units of work.

2. Urgent and Impactful: “This is your next task!”

There’s nothing more impactful or urgent than these things. If it’s a problem, it can’t escalate any further because it’s already at its worst… an example is a critical bug in our production environment. If we’re referring to new tech or product initiatives, that’s the one that will benefit your users the most… for example, the ability to edit messages in a chat app, or the ability to tip the courier in a food delivery app. These are things that usually take a lot of time to implement, but are of great benefit to both the users and our organization.

3. Not Urgent, but Impactful: “Put on the Radar”

You know this will have a big impact, but you’re not ready for it. You don’t know where the market will go, how technology will evolve, who’ll block you or unblock you… but you know for sure that it’s going to be a big deal. Some examples that come to mind are: try a new programming paradigm (reactive and functional programming), try a new monitoring tool (ELK stack and Prometheus/Grafana), cross-platform technology, etc.

4. Not Urgent and Not Influential: “Decline!”

Nothing and no one is forcing you to act quickly. The impact isn’t clear, or it’s clear that the impact is small. Some examples that come to mind are: Adding or removing an app component that’s not been analytically captured or analyzed in user research (i.e., the impact is unclear), adding or changing a feature for the sake of change (i.e., the impact is potentially negative), refactoring a rarely used system or service (i.e., the impact is minimal), etc. So the point isn’t that this shouldn’t be done at some point… it should… it just doesn’t have enough impact compared to other things on the table.

— What would you do if you couldn’t make your own decisions about priorities?

(you ask)

I don’t make those decisions on my own anyway. And, of course, I don’t always apply this basic framework to everything. It’s just a good starting point for setting the right priorities, if you’re willing to be honest with yourself and aware of your environment. I still ask my colleagues for feedback, talk to the teams I work with, interview stakeholders, cost center managers, product leads… and finally get everyone’s input before I make a decision.

It’s always good to have data at hand, because without data it’s hard to argue with people holding more “power” than you. In my personal life, I do more or less the same thing - my wife is my main sparing partner, so it’s not a solo effort here either.

💭 Reminder: Progress is impossible without change, and change is impossible without someone driving it.

— What if I have too many things in one of the categories?

Well, I usually just focus on the first two categories. If there’s too much going on in one of the first two categories, I apply the same prioritization process within the crowded category.

💭 Reminder: When everything is important, nothing is important.

— How do you know if you have time for something?

— How do you justify not doing everything that comes your way?

I plan getting things done backwards, even though I realize I can’t plan for all the tiny details. But most things can be planned backwards, because with enough experience it’s possible to anticipate and react to problems before they occur.

What does this mean in practice?

Imaginary example. Let’s say we’re working on user proximity detection and reporting with GPS from your app, trying to detect clusters of users. We’re now at November 1, but let’s assume we want to complete this initiative before the end of January.

Starting backwards from February 1 (with imaginary dates, estimates, and milestones):

It appears that there’s no (or little) time for:

Not to mention, the team doesn’t sit idle for weeks waiting for approvals. Engineering resources are scarce and unchanging. If 6 things are running in parallel and people are constantly jumping between issues, some of those issues are bound to be delayed. All the scheduling combined with changes in priorities has a big impact on the final roadmap.

The Final Decision: Either discard this or something else (keep only the highest priority things)!

Thanks to this process, I can communicate planning issues clearly and transparently, and it’s clear why most things need to be rejected.

💭 Reminder: Optimize to get a few things right instead of optimizing to look busy.

— If your team had a 5-year roadmap, what would you do?

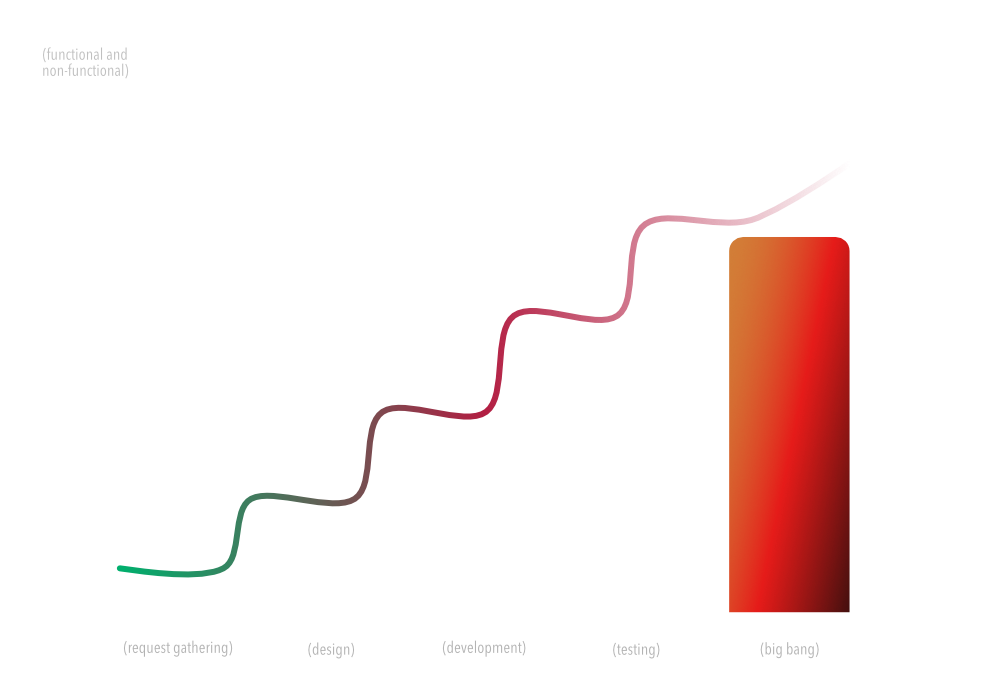

This is a tough question. A long roadmap is basically a long-term product commitment, and that’s a good thing for a product. Unfortunately, anything long tends to accumulate risk over time, and Agile/Lean organizations are generally better at risk management. I am referring to the good old Agile risk management chart.

Traditional risk management chart

Traditional risk management chart

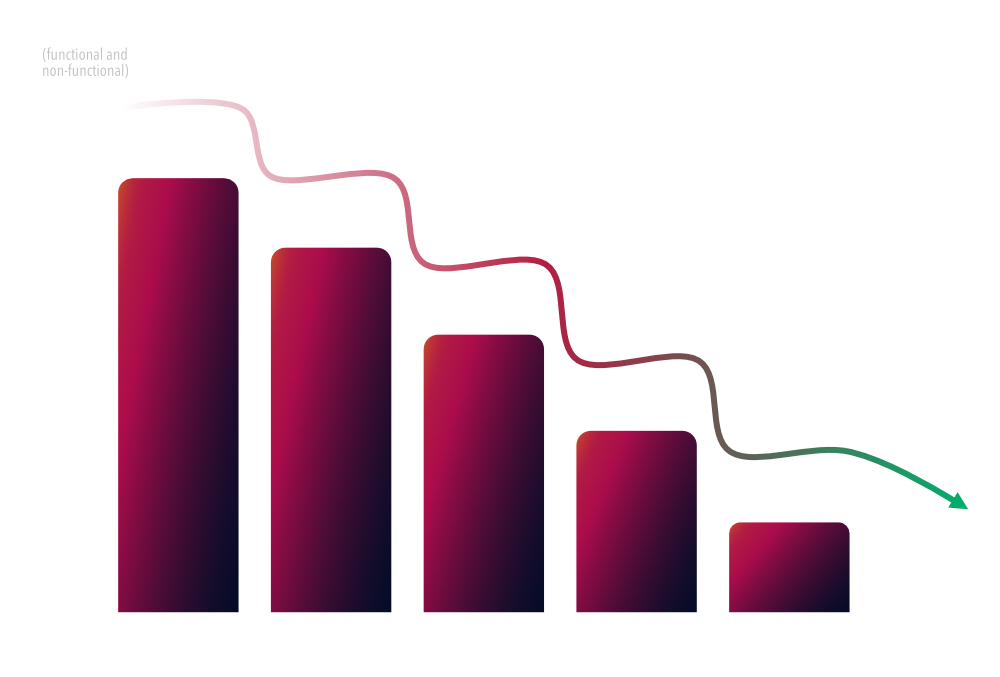

Agile risk management chart

Agile risk management chart

To combat these risk challenges and ensure we’re better serving our stakeholders, most teams I work with have recently implemented a Continuous Planning process. Of course, every implementation of this process is different. But from my perspective, I see it as more agile, an iteration of the agile approach to risk reduction applied to the entire roadmap (rather than a single product).

For each individual case, I’d recommend looking at product release risk history, launch cadence, other DORA metrics and similar data points to decide which process is best. It may be that a long roadmap is better for the team, although that’s rarely the case.

The best read on this so far:

This goes hand in hand with the basic framework I described above. Again, engineering resources don’t just simply grow when you need them, so it’s not possible to make up engineering time that doesn’t exist. That’s why I think it’s very important that people in the environment understand the constraints of each team member… to be clear, I have limited time to work, limited team resources, and a pretty fixed schedule. This framework ensures that I finish my work on time (or almost on time), which in turn guarantees that I have time for a life outside of work as well.

I’m a firm believer that all requests, inquiries, and questions (personal or professional) deserve a response – at least to communicate that I’m busy. It takes almost no time to reply “I’m busy right now, let me get back to you later”, so I try to at least do that whenever possible. But if I’m having a really busy day, I’ll set my Slack status to busy – then the messages often don’t come at all, because people immediately see that I’m busy.

Example of a Slack profile with DND mode and Calendar status

Example of a Slack profile with DND mode and Calendar status

There’s more to this in the rest of this series.

It’s really hard to prioritize, and I can’t stress enough that there’s no silver bullet. As we part ways here, I’d like to leave you with a nice quote from the man who grew Intel into a successful and healthy corporation:

My day ends when I am tired and ready to go home, not when I’m done. I am never done. There is always more to be done, more that should be done, always more than can be done.

Andy Grove

I think what he says here is counterintuitive; he’s not saying that we should work all day, but rather the opposite. We should aim to do what we can in high quality and then go home. That’s a good attitude to have.

Recommended reading (by the same author):